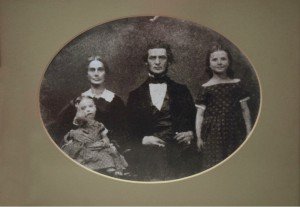

Undated photograph of Charlotte, Obed and two daughters. Print used courtesy First Congregational Church of Salem. Oregon

In her journal entry of January 24, 1853, Charlotte Dickinson wrote of a shipboard encounter with a black cook. “He is a Christian and I felt that he was truly a child of Our Heavenly Father. O, it did my heart good to hear him talk while the tears streamed down his dark face. And how earnestly he did plead to be remembered in our prayers as he took our hand and clung to it long.” It would be ten years before Charlotte was able to put her concern for African-Americans, especially their education, into action.

Charlotte and Obed Dickinson had been newly-weds in November of 1852 when they embarked on the long voyage around the Horn to his assignment as a Congregational minister in frontier Oregon. Landing in Portland the following April, they had personal baggage and simple furnishings for their home: a stove, table, chairs and bedding. It took them eighteen days to transport their belongings and themselves by boat and cart to Salem, a village of 500 people, ten dry goods stores, four physicians, a flouring mill, various mechanics – and five other ministers, all Methodist.

His church was an abandoned schoolhouse at Commercial and Marion Streets described as “dirty as a pig sty, its floor covered with mud.” Boarding was too expensive, so Obed purchased a half acre of land, deep in the brush between Front Street and the river, for a small 16 x 26 feet home. As the young minister was building his house, he planted apple trees and a garden. He and Charlotte were broke, living on little or no income. “Not a crust of bread nor a baked potato has been lost,” he wrote. “Everything has been cooked in some way for our food.” He wrote letters urging the Missionary Society to send him help: “I am now so much in debt that I almost feel ashamed to meet a man in the street.” Their poverty would continue as long as his ministry.

Charlotte was not in good health, suffering from a “spinal problem”. Obed ordered her medicine: bottled petroleum to be used as a lineament. “Many of our friends feel they are indebted to it for their lives and present health,” he reported. “Several are suffering from the same diseases from which it has freed her.” Motherhood brought her additional problems. The second of their two daughters, Alice Amelia, lived only a year. Of four children, only Cora, the eldest, survived. They also adopted a daughter.

The greatest professional conflict the Dickinsons faced was their continuing interest in the Negroes of Salem, a group not accepted by the other churches. This concern was translated into action at the worst possible time: while they were building a new church and trying to expand their church membership. As Obed preached against the sins of slavery and the mistreatment of the local black population, he actively encouraged Negroes to join his church. Funds dried up, membership declined. Church supporters requested separate services, a New Years party which blacks attended was a cause of malicious gossip, a negro wedding conducted by Dickinson was considered a scandal. As Negroes were not allowed to go to school, Charlotte undertook their instruction in her home. Dickinson wrote, “Daily, at evening, a company of four (with a fifth as often as her mistress will allow) may be seen for two hours, as intent and earnest over their books as any white children you can find. And, what is better, my wife who has taught school for fifteen years, says she has never seen such rapid improvement. They labor under great disadvantages for one is a wife, and has all the cares of a family, and two others are servant girls, yet they are all beginning to read intelligibly. Three have learned their figures and are going on well in the first questions of mental arithmetic. All this in five weeks.”

The church did get built, although Dickinson continued to preach against the sins he found around him including what he called the “liquor interests.” He refused to be censored, and paid the price of idealism in the practical community of Salem. He resigned his pastorate in 1867, devoting his energy to his skills in farming, developing a seed business and a nursery. His business prospered and for the next fifteen years he built respect for his character and business integrity. Obed Dickinson died June 15, 1892. Charlotte’s grave in Pioneer Cemetery is beside his, dated October 15, 1893.

Cora graduated from Willamette University and married A. N. Moores on 26 May, 1885. They resided at 885 Chemeketa Street with their three children, Kenneth, Althea and Ralph. Mr. Moores died in 1935 and Cora in 1938. Their home was relocated in 1951 during the development of the North Capitol Mall and now stands at 920 Leffelle Street.