Most of us have had an acquaintance (or member of the family) like Margaret Jewitt Smith. She was, to put it in more a modern-day term, “ahead of her time”. Even today, when a woman in America has more choices in her future than Margaret could have imagined, there are those who seek unconventional paths. She saw herself as more than the wife and mother her society demanded of her future: she wanted to express herself as a writer of poetry, to have a career as a teacher, to see the world. She might have even had aspirations to vote! She said “No” to the limits of domestic life, always under the control of men, offered women of her time.

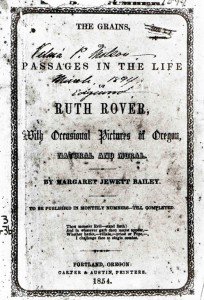

Margaret discovered Dr. Bailey was not an ideal husband: he had a violent temper and was alcoholic. However, by 1848 her writing career was advancing as her poetry (signed by MJB) was appearing in the Oregon Spectator. She was even hopeful of editing a periodical for women. Realizing her personal situation with an abusive husband could not continue, she divorced Dr. Bailey in 1854. That same year her book, with the lengthy title of Grains, or, Passages in the Life of Ruth Rover, with Occasional Pictures of Oregon, Natural and Moral was published. In Chapter One the narrator as Ruth Rover reveals, “I am avoided and shunned, and slighted, and regarded with suspicions in every place till my life is more burdensome than death would be. I have, therefore, … been impelled by a sense of justice due to myself and a wish that my future life should not be overshadowed by the gloom of the present.”

This thinly disguised narration of her life at the mission changed the names of the missionaries in the novel, but revealed them in copies of actual documents inserted in the text along with her poems. Of course, this was too much! A divorced women casting suspicion on the motives and behavior of the ministers! Amid public criticism, her career as a published Oregon writer came to an end.

Much of this information is found in the Oregon Encyclopedia under the title “Margaret Jewett Smith Bailey (1812-1882)”.

William Bailey went on to participate in Oregon’s provisional government, living on his property in the French Prairie of the Willamette Valley with his second wife. He is buried in the St. Paul Cemetery.

Photograph: Oregon Historical Society, Research Library, ORHi37311

One Comment